What does neuroscience have to do with creativity? Plenty, if you want to cut through the clutter and focus on really bringing that creative vision to life. Adam Gazzaley, M.D., Ph.D, is both a neuroscientist and a published author and photographer. He’s currently leading a company called Neuroscape that’s in the process of FDA approval for technology that uses video games to improve attention spans in kids with ADHD. He recently sat down with CreativeLive Founder Chase Jarvis to discuss how a basic understanding neuroscience can help improve creativity.

The interview is well worth a full listen, but if you only have a five-minutes for Gazzaley, here are the six key takeaways to use in your own creative process.

Controlling your brain fosters creativity.

The brain is a creative muscle — and while we may not be able to control exactly what ideas come from those creative sessions, we can encourage creativity to happen more often by understanding the brain. Borrowing a few ideas from neuroscience, creatives can engage in exercises to foster creativity, build creative habits and build an environment where creativity thrives.

Understand your own brain — and both what you are good at and not so good at.

The first step to training your brain to foster creativity, Gazzaley says, is to understand what makes you different — what is your brain good at, and what is it not so good at? Maybe you’ve gotten so good at multitasking that when it comes time to sit down and create, you can’t focus on a single task alone. Or maybe you have big ideas, but every time you sit down to turn them into something real, anxiety holds you back. Starting by recognizing your strong and weak points helps identify the changes that will work best for your creative process.

Work out the steps to overcome your own weaknesses — and leave enough time.

Once you understand what is hindering your creativity, you can create attainable steps to remove those obstacles. Start small and leave enough time — overcoming creative hurdles isn’t something that happens overnight. A small step for overcoming the urge to always be multitasking is to start with focusing on a single short task and working your way into turning off the distractions for an hour or more at a time, for example.

Embrace boredom and single-tasking.

One of the reasons creativity is often squelched? Never being bored, Gazzaley says. We pull out our phones for the three-minute wait in line to get coffee, on commercial breaks and any other time where boredom starts creeping in. But boredom is where creativity happens, Gazzaley says, in those small moments when you aren’t bringing in any new information. Instead, spend those three minutes in line at the coffee shop being bored, taking in the smells and the hiss of the espresso machine — let the boredom come and the ideas will follow.

Bring interval training into creativity with short breaks.

Interval training is a common idea in fitness: mix intense bursts of exercise with lighter work then go back to that intense burst. The same idea, Gazzaley suggests, can be applied to cognitive exercises. Take short breaks in the middle of those creative sessions. Not the kind of breaks we’re accustomed to like looking at our phones, checking email, and social media, however. Gazzaley suggests taking a minute to do ten pushups or another short physical activity. Mixing a creative exercise with a short physical one often fosters that creativity.

Practice mindfulness.

Just like meditation as a cognitive exercise can reduce anxiety, mindfulness is a cognitive exercise that promotes creativity, Gazzaley suggests. Mindfulness is simply paying attention — start with something as simple as paying attention to everything as you eat, the way the food tastes, feels, smells and the movements of your mouth. Or, practice mindfulness during another daily routine, like focusing on the movements of your own body and your breathing during exercise. Mindfulness is a sort of mediation that drives interaction with the people and things around you. Mindfulness isn’t something you can practice 24/7, but it is something we can remind ourselves to practice more often, Gazzaley suggests.

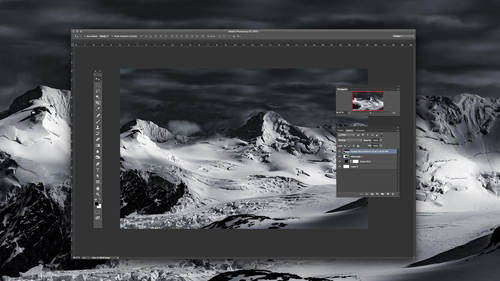

Gazzaley says that photography itself taught him how to be mindful of his own emotions while running a landscape photography venture 20 years ago. Whenever he tried to shoot an image based on technical rules alone, the result fell flat, but whenever he let his emotions guide his decision on what to frame within the composition, he created an image that could also spark emotion in the viewer. He says the exploration in his nature photography still shares ties with his exploration in the lab researching non-pharmaceutical treatments for a variety of cognitive conditions.

“The work that we do is the foundation of creativity,” Gazzaley says, “the ability to have control over your own mind is where it starts.”

Check out the complete interview over on Chase’s site.