Almost 30 years ago, Adobe changed the way we view photo manipulation with the release of Photoshop, a software that, at the time, was predicted to sell maybe 500 copies, tops.

Because, though plenty of publishers and advertisers were beginning to eye the advantages of doing things digitally, the world was still very much centered in the analog — which meant that most photos were still being edited the old-fashioned way.

In a 2013 blog post for Fstoppers, professional retoucher Pratik Naik described the painstaking process as such:

“Need to zoom into a photo? Be sure to bust out the magnifying glass and a bottle of patience along with that steady hand of yours. No sorry, there’s no history states or layers. You can also forget about that wonderful healing brush! Here’s a paint brush instead”

Art directors, graphic designers, and publishers labored long hours over images, attempting to perfect skin, materials, and other issues which, today, would be easily whisked away with the click of a mouse. Tools like paint, erasers, airbrushes, and other art supplies were necessary in any studio — as was a steady hand and a keen eye for color and shadow. You can even see some of the hard work that went into perfecting photos in this annotation of a famous Dennis Stock image, which has been marked up by Pablo Inirio.

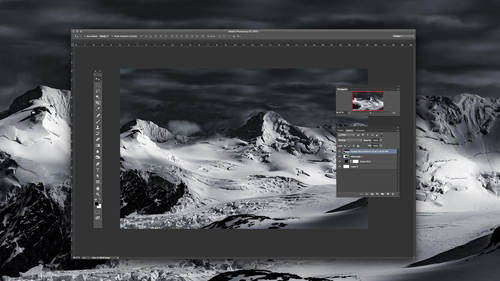

Are you ready to turn your photograph into a work of art? Lisa Carney shows you how in her latest class, Working with Brushes in Photoshop CC. Learn more.

However, photo editing certainly wasn’t limited to the occasional pen stroke; other, more extreme forms of photo manipulation have been giving photographers and other interested parties the ability to change our perception of reality.

Discoveries like the wet collodion process, which allowed photographers to combine multiple images on one negative, captivated the curiosity and creativity of photographers dating back to the 1850s. And, much like today, sometimes the tricks of the trade were used for, well, trickery.

“Spirit photography,” which largely preyed on the grieving families of fallen Civil War soldiers, claimed to capture “photographic proof” of spirits — most famously, William H. Mumler’s images of Abe Lincoln, whose spirit appeared to be lingering behind his widow, Mary.

Mumler was charged with fraud over the images, though he was never prosecuted. Still, his legacy persists, as he remains one of the most famous purveyors of altered photos claiming to capture the spirit world.

Photo manipulation was also used early on as a form of whimsy. So-called “tall tale” postcards were popular instances of retouching from around the turn of the century. Frequently credited to photographers William H. “Dad” Martin and Alfred Stanley Johnson Jr., these images were cut up, cropped, and mass-produced as tourism items, often featuring giant plants and animals, unusual “feats of strength,” and other oddities — which, to a public who weren’t used to seeing altered images, were quite captivating.

Photoshop was also certainly not the beginning of photographs that tell only a part of a story — or a story that’s been fabricated entirely. In the archives along with “Portrait of the Photographer as a Drowned Man” and the famous Cottingley Fairies (two of the first major photography-based hoaxes), there are lesser-known instances of photo manipulation that had nothing to do with changing a photograph itself or even really fooling anyone, but rather, were created by staging a photo for the sole purpose of increasing the dramatic effect. The above image, for example, contains elements from multiple photos from thee Battle of Zonnebeke in Belgium during WW1.

In an episode of the WYNC show Radiolab, hosts Jad Abumrad and Robert Krulwich speak with documentarian Errol Morris about a photo (and a potential photo manipulation) that has bedeviled him. A photo, taken during the Crimean War in 1855 and titled “The Valley of the Shadow of Death,” contain a kind of mystery.

“As Errol explains, it turns out there were actually two photos — both taken from the same spot over 150 years ago. One image famously shows a road littered with cannonballs, while the other shows the same road with no cannonballs (they’re off to the side in ditches). Which one came first? And why would the cannonballs have been moved?”

Had one or more of the photos been edited, or just staged?

As it turned out, the photo was staged.

“In addition to being one of the first photographs of war,” explains Jad, “this was also one of the first photographic lies.”

Optical engineer Dennis Purcell explained the staging as a way for the photographer, Robert Fenton, to make the image “look the way it felt” to be there, on the ground, during the war. He, himself, had moved the cannonballs onto the road to give the image a greater impact.

The question of early photo manipulation is clearly a captivating one; edited photos were even the subject of an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. And while many instances were clearly designed to trick the public, that was certainly not always the case.

Are you ready to turn your photograph into a work of art? Lisa Carney shows you how in her latest class, Working with Brushes in Photoshop CC. Learn more.

“Most of the earliest manipulated photographs were attempts to compensate for the new medium’s technical limitations — specifically, its inability to depict the world as it appears to the naked eye,” explained Mia Fineman, an assistant curator of photography at the Met and the author of the exhibition’s accompanying catalog in an interview with PBS.

Photoshop, she says, is the “latest tool” for photographers, but it’s certainly not the one that invented photo manipulation.

“Photographers have always used whatever technical means were available to them to create the pictures they wanted to create,” she explains.

Top image: “A set of retouching tools for manipulating photographs (retouching ink, retouching paint, airbrush, etcetera),” via the Nationaal Archief fotonummer on Flickr